Tyndall Stone is one of Canada’s iconic building stones. Derived from near Garson, Manitoba, it is used in a great number of buildings in Winnipeg. However it shows up all over the place as a high quality and attractive stone, suitable for both exterior and interior use with honed, bush-hammered or a polished surface. With a compressive strength of 62.8 MPa, it is a very strong and durable construction limestone.

Tyndall Stone is extracted from the Selkirk Formation of the Red River Group of the Williston Basin. Tyndall Stone is quarried at Gillis Quarry in south western Manitoba, but extends westwards into Saskatchewan where the lateral equivalent is known as the Yeoman Formation. These formations are overlain by evaporite deposits. Gillis Quarry exposes a 43 m thick unit of massive, metre-thick beds and have allowed excellent exposures for 3D scientific study of this stone. The rock is of Upper Ordovician (Katian, 445-453 Ma) age.

The Gillis Quarry is located around 40 km northeast of Winnipeg (see Google Maps). Most sources seem to agree that the first use of this stone was at Lower Fort Garry built in the 1830s. Gillis Quarries were brought into commercial production in 1910 and have remained in the same family ever since. The stone lends itself well to both traditional and modernist architectural styles, with finishes ranging from rough, quarry-dressed blocks to smooth, honed or polished ashlars.

Tyndall Stone is a limestone, but with a significant dolomite content.

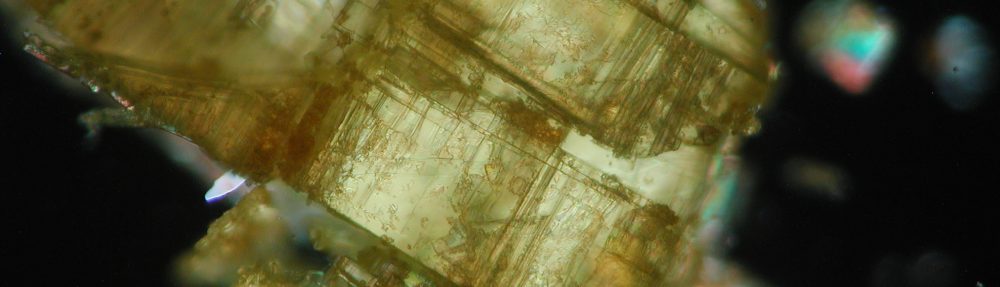

The most striking thing about this stone – and its main decorative feature – is that it is pervasively riddled with Thalassinoides trace fossils. These are branching burrows, with T- or Y-shaped junctions made by creatures tunnelling through the soft sediment, which are typically 1 to 2.5 cm wide. These show up brown in contrast to the cream-coloured limestone matrix, this is because the burrows backfilled with dolomite. It is not known what made these burrows during the Upper Ordovician, but modern Thalassinoides burrows are made by the shrimp Callianassa so a similar crustacean is a reasonable guess (Jin et al., 2012).

Many other fossils are present and abundant in these strata and have been described by Jin et al. (2012). The Receptaculitid Fisherites reticulatus (Finney & Nitecki, 1979) is a spectacular component of this rock, and if it were needed, a distinguishing feature of Tyndall Stone. Up to 25 cm or so in diameter, these are circular fossils with a scaly appearance, appearing like the seed head of a sunflower. They are assumed to be fossilised calcareous algae.

Also present are very large Nautiloids. These include orthocones as thick as my arm and indeed called Armenoceras. This genus along with Endoceras can be over a metre in length.

The coiled Nautiloid Wilsonoceras which can reach diameters of 40 cm is also present.

These cephalopods are diagnostic of the so-called ‘Arctic Cephalopod Fauna’ and are typical of these late Ordovician carbonate platforms.

Other molluscs include gastropods, such as the planispiral Maclurina and the cone-spiralled Hormotoma.

Tyndall Stone with Thalassinoides at the Fairmont Chateau Lake Louise. A possible planispiral gastropod can be seen at bottom right.

Corals are also present. This is probably the tabulate coral Catenipora.

Rugose corals include the varieties Grewingkia, Crenulites and Palaeophyllum.

Other reef-forming organisms in addition to corals and Receptaculitids are stromatoporoids of which I found only fragments.

The Tyndall Stone-type of Thalassinoides facies is regionally widespread throughout the Upper Ordovician strata of Laurentia, with very similar formations existing in Greenland (Børglum River Formation), as well as in Canada and the USA (i.e. Bighorn Dolomite of Wyoming; see Jin et al., 2012; Gingras et al., 2004; Sheehan & Schiefelbein, 1984).

As a good quality freestone, Tyndall Stone has also been used for carving by a number of artists and it even gets a mention in literature. Canadian author Carol Shields described Tyndall Stone in her, perhaps predictably titled, novel ‘The Stone Diaries’; “Some folks call it tapestry stone, and they prize, especially, its random fossils: gastropods, brachiopods, trilobites, corals and snails. As the flesh of these once-living creatures decayed, a limey mud filled the casings and hardened to rock”

Urban Geology guides and descriptions of Tyndall stone buildings in Winnipeg are available by Thorsteinson (2013) and on Donna Janke’s Blog ‘Destinations, Detours & Dreams’.

Tyndall Stone is widely used throughout Canada, but as far as I know, has yet to make it to the UK … I looked at the following buildings during my recent trip to Vancouver and Banff National Park.

In Vancouver, the Tyndall Stone-clad Terminal City Club is on West Hasting’s street and the same building occupied by the Lion’s Pub fronting onto West Cordova Street.

In Banff National Park, the Fairmont Chateau Lake Louise has Tyndall Stone cladding on the ground floor and the Fairmont Banff Springs uses polished Tyndall Stone as paving, cladding and dressings in the impressive entrance hall.

My Sister, thrilled at finding the Receptaculitid Fisherites on the Terminal City Club in Vancouver. It is on the slab above the right side of the porch.

All photos used here are by Ruth Siddall and should be cited as such.

To cite this article:

Siddall, R., 2017, Tyndall Stone: An Iconic Canadian Building Stone., Orpiment Blog, published 09/09/2017: http://wp.me/p53QQu-bC

References and further reading

Finney, S. C. & Nitecki, M. H., 1979, Fisherites n. gen. reticulatus (Owen, 1844), a New Name for Receptaculites oweni Hall, 1861., Journal of Paleontology., 53 (3), 750-753.

Gingras, M. K., Pemberton, S. G., Muelenbachs, K. & Machel, H., 2004, Conceptual models for burrow-related, selective dolomitization with textural and isotopic evidence from the Tyndall Stone, Canada., Geobiology, 2, 21–30.

Jin, J., Harper, D. A. T., Rasmussen, J. A. & Sheehan, P. M., 2012, Late Ordovician massive-bedded Thalassinoides ichnofacies along the palaeoequator of Laurentia., Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 367–368 (2012) 73–88.

Kendall, A.C., 1977. Origin of dolomite mottling in Ordovician limestones from Saskatchewan and Manitoba. Bulletin of Canadian Petroleum Geology, v. 25, p. 480-504.

Sheehan, P.M. and Schiefelbein, D.R.J., 1984. The trace fossil Thalassinoides from the Upper Ordovician of the eastern Great Basin: deep burrowing in the early Paleozoic. Journal of Paleontology, v. 58, p. 440-447.

Shields, C., 1993, The Stone Diaries., Fourth Estate., 361 pp.

Thorsteinson, J., 2013, Tyndall Stone., Winnipeg Architecture Foundation Inc., 13 pp.