Field notes on some Broadland churches in the Wroxham area, Norfolk.

Ruth Siddall, January 2019.

The building stones of Broadland Churches visited by Ruth Siddall and Tim Atkinson on 12 January 2019. Please regard these as field notes; they are not intended to be exhaustive or complete records of the fabric of the churches described below.

St Peter’s, Belaugh

TG 2890 1841

12thCentury with 15thCentury alterations and 19thCentury restoration by Butterfield & Phipson.

Rubble Masonry: Coarse flint, ferricrete, Wroxham Crag[1]component (minor), beach flints (minor).

Course flints retain cortices and may be very large > 30 cm long-axis single flints (NB very large flints are also used as gate posts in the village).

Ferricrete (very dark brown – almost black, pebbly [angular, moderately sorted], friable and rarer pieces of rust-red pebbly variety, with stratified pebbles). The dark ferricrete is used for quoins on NE corner and for (filled) window dressings on the north wall and as squared blocks in the lower part of this wall. These are probably from the 12thCentury phase and the ferricretes blocks are possibly reused. Ferricrete blocks have developed a pale green-white encrusting limestone.

Wroxham Crag component: white vein quartz cobble (south wall, close to door).

15thCentury rubble masonry includes a few slabs of Barnack Stone on west wall. Clipsham Stone dressings on windows of this period?

19thCentury – Knapped flint work with Ancaster Stone dressings. Uncoursed, coarse flint with cortices. Some Conulussp. echinoids. Some coursed, square-knapped flint work on buttresses.

Interior: Font (12thCentury) – grey green, fine grained limestone with a few white bivalve fossils. Unidentified stone.

North facing wall of St Peter’s Church, Belaugh showing several phases of construction and restoration and the distinctive, almost black blocks of ferricrete.

North facing wall of St Peter’s Church, Belaugh showing several phases of construction and restoration and the distinctive, almost black blocks of ferricrete.

Knapped flints from the south facing wall containing a Conulus sp. Echinoid.

Knapped flints from the south facing wall containing a Conulus sp. Echinoid.

Blocks of ferricrete along with unknapped, uncoursed flints in the south wall of St Peter’s Church, Belaugh. These stones have been recycled into restoration phases.

Blocks of ferricrete along with unknapped, uncoursed flints in the south wall of St Peter’s Church, Belaugh. These stones have been recycled into restoration phases.

Ferricrete used as quoins and ashlar on the NE corner of the church.

Ferricrete used as quoins and ashlar on the NE corner of the church.

St Helen’s, Ranworth

Woodbastwick Road, Ranworth, Norfolk NR13 6HS

TG 3560 1476

First phase 1290-1350, Second Phase (Perpendicular-style alterations) up to 1530. Rood Screen 1419. North side of the church is much colonised by lichen.

Carved plinths (lamb of God, shields) on buttresses – Clipsham or possibly Barnack Stone.

Quoins, tracery and other dressings: Clipsham Stone

Rubble Masonry: Coarse flint, ferricrete (bright red-orange), Greensand (minor), Wroxham Crag component (vein quartz, Triassic quartzites, chatter-marked flints).

Flints – coarse with intact cortices, some knapped. Probably some are field flints. Upper parts of the building, including the tower have a large amount of red-orange flints. A circular, red flint in the tower (south side, c. 12 m up) is a paramoudra. Square, knapped, coursed flint work on foundations and buttresses.

Red-stained flints on the tower at St Helen’s, Ranworth including a ring-shaped paramoudra from the local chalk

Red-stained flints on the tower at St Helen’s, Ranworth including a ring-shaped paramoudra from the local chalk

Red-stained flint with fossil echinoid.

Red-stained flint with fossil echinoid.

Ferricrete is a bright orange red cemented gravel with rounded to sub-rounded, poorly sorted, flint pebbles up to 4 cm long axis. Some blocks are of a gritty sand with sparse pebbles.

Blocks of ferricrete at St Helen’s Church, Ranworth.

Blocks of ferricrete at St Helen’s Church, Ranworth.

The ferricrete has variable texture and clast size/distribution. However, it is notably a bright. Brick red in colour.

The ferricrete has variable texture and clast size/distribution. However, it is notably a bright. Brick red in colour.

Wroxham Crag component: cobbles of vein quartz and red-pink Triassic Bunter pebbles (fist size) are common within the fabric, as are rounded, chatter-marked beach flints.

Vein quartz cobbles from the Wroxham Crag at St Helen’s, Ranworth.

Vein quartz cobbles from the Wroxham Crag at St Helen’s, Ranworth.

Spolia: a few rough fragments of Barnack Stone and a fine-grained Caen Stone pilaster. Greensands (possibly Kentish Rag) occur in a few squared blocks. These are possibly spolia or ballast.

Small pillar of Caen Stone spolia.

Small pillar of Caen Stone spolia.

Greensand block, probably spolia or ballast.

Greensand block, probably spolia or ballast.

Interior: grave slab of Green Purbeck Marble (with Uniosp.) flanked by smaller slabs of Red Purbeck Marble. Also slabs of 18thCentury of black Lower Carboniferous limestone with small white rugose corals, sparse brachiopods and a gastropod. This is probably Belgian or Irish in origin.

Green Purbeck Marble grave slab with thick walled, Unio sp. Bivalves inside St Helen’s Church, Ranworth.

Green Purbeck Marble grave slab with thick walled, Unio sp. Bivalves inside St Helen’s Church, Ranworth.

St Mary’s, South Walsham

23, The Street, South Walsham NR13 6DQ

TG 3653 1325

First phase 12th-13thCentury but much is 13th-14thCentury. Tower and porch are 15thCentury. Heritage Norfolk states ‘This church has a large quantity of lava incorporated into the walls along with reused masonry.’ I have no idea what the ‘lava’ refers to!

Lower courses (C12-13) of coarse flints with cortices intact, roughly coursed. Upper parts of knapped, uncoursed flint with spolia. The latter is composed of slabs of Purbeck Marble (much weathered, but with clear Viviparussp., 10 cm thick, c. 30 cm long) occur about 1 m up from foundations in the south and east chancel walls. Also, a fragment of carved, spoliated capital in Caen Stone or Clunch to the west of the down pipe of the buttress between the nave and chancel on the south side.

Exotic pebbles: sub-angular, brown, quartz arenites. These may be derived from the Crag or tills or could be ballast. Possibly striation on one example suggests till.

Porch: Square knapped, coursed flint flushwork with Clipsham Stone dressings (15thCentury).

Unknapped, beach flints have been added to the top of the walls of the north porch, probably in in the 19thCentury.

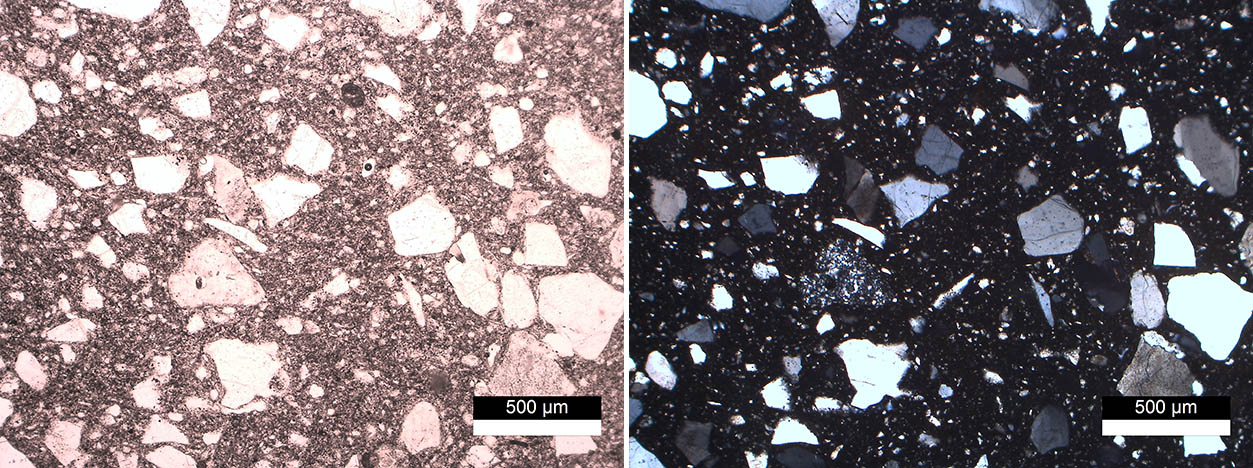

Knapped, coarse flints with boulders of brown arenaceous sandstone at St Mary’s, South Walsham.

Knapped, coarse flints with boulders of brown arenaceous sandstone at St Mary’s, South Walsham.

The photo above shows a boulder which may show evidence of glacial striae.

The photo above shows a boulder which may show evidence of glacial striae.

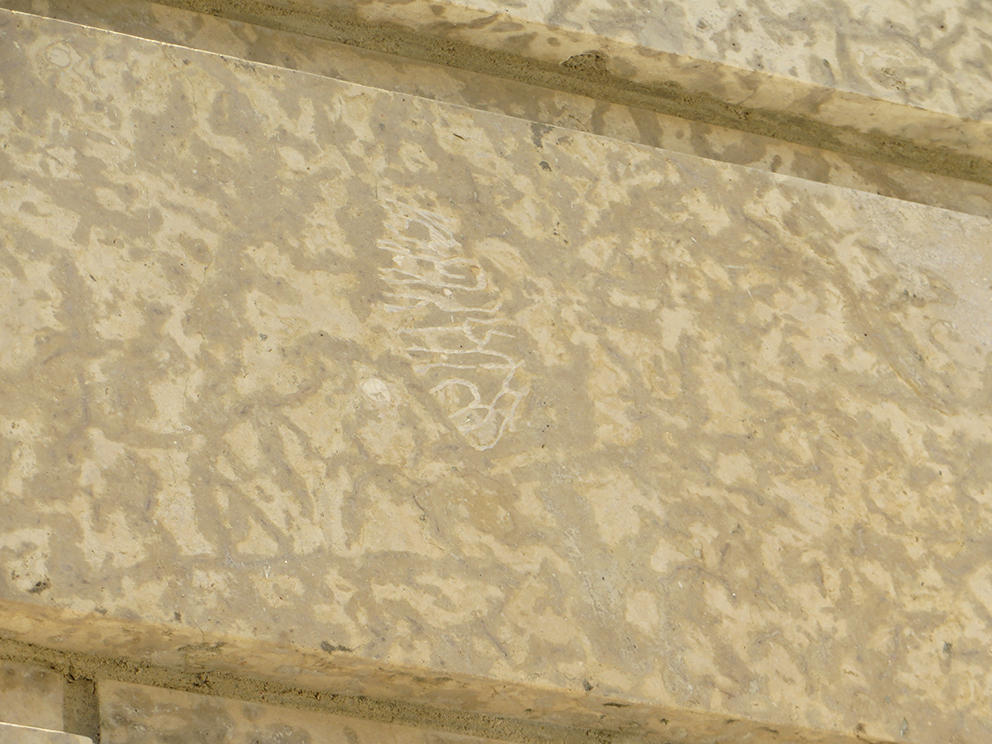

St Mary’s Church, South Walsham. Fragment of carved capital in Caen Stone used as spolia in the church’s fabric.

St Mary’s Church, South Walsham. Fragment of carved capital in Caen Stone used as spolia in the church’s fabric.

Slabs of Purbeck stone, weathering in are laid in a line across the centre of the photograph.

Slabs of Purbeck stone, weathering in are laid in a line across the centre of the photograph.

St Lawrence’s, South Walsham

The Street, South Walsham NR13 6DQ, located next door to St Mary’s (above)

A 14thCentury Church restored in 1992. This building was visited very briefly.

Knapped, uncoursed flint work with Clipsham Stone dressings.

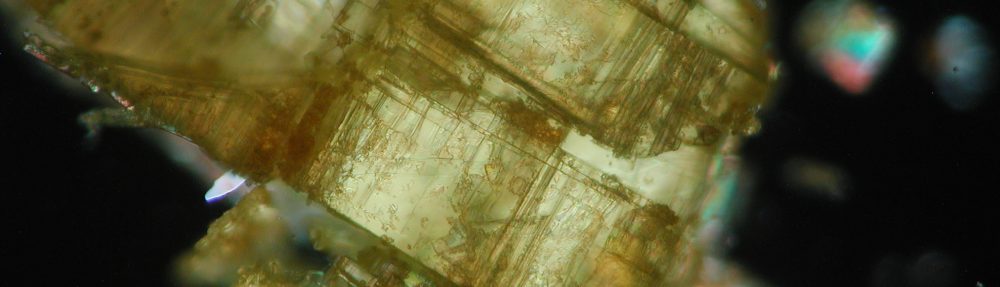

Stonework at St Lawrence’s, South Walsham; detail of Clipsham Stone dressings; this cross-bedded calcarenite is packed with shell fragments.

Stonework at St Lawrence’s, South Walsham; detail of Clipsham Stone dressings; this cross-bedded calcarenite is packed with shell fragments.

Knapped flint cobbles.

Knapped flint cobbles.

All Saints, Hemblington

Church Lane NR13 4EF

TG 35 11

Saxon-Norman Round Tower, chancel c. 1300, nave c. 1400 with 15thCentury roof and wall-paintings (of St Christopher).

Walls are predominantly of unknapped, coursed flint with cortices intact. Some (faint) herringbone coursing. Some knapped flint.

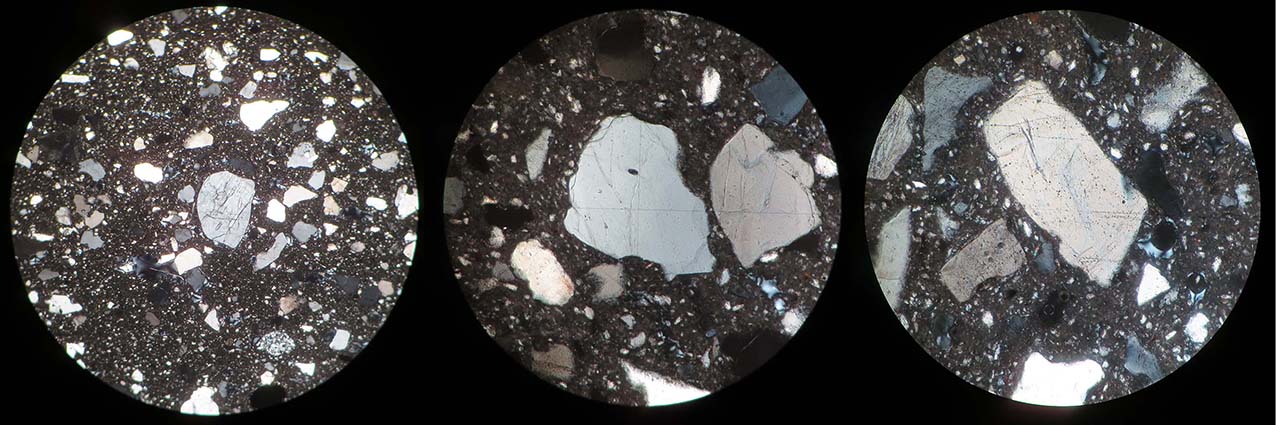

Exotic cobbles: Abundant, well-rounded quartzite (Triassic) pebbles and also sub-rounded to sub-angular cobbles of brown arenaceous sandstones, probably from Wroxham Crag and related deposits. Also a few one-off finds i.e. Hertfordshire Puddingstone sarsen, a medium-grained diorite.

Abundant spolia in Caen Stone is present. The Tudor brick window on the tower is cut into what was probably a spoliated window sill in Caen Stone. There is also a large amount of brick and tile incorporated into the walls.

Flushwork, knapped flint crosses on either side of the south porch entrance.

Dressings on buttresses in Lincolnshire Limestone (not fully observed).

The east end of All Saints Church, Hemblington showing at least two phases of construction.

The east end of All Saints Church, Hemblington showing at least two phases of construction.

Flushwork flint crosses in the brick-built south porch.

Flushwork flint crosses in the brick-built south porch.

Carved spolia and rough flints in the walls.

Carved spolia and rough flints in the walls.

Carved spolia in Caen stone. This is the remains of a window sill which has been cut into by Tudor brick work (on the left of the image).

Carved spolia in Caen stone. This is the remains of a window sill which has been cut into by Tudor brick work (on the left of the image).

Detail of stones at All Saints Church, Hemblington. Triassic quartzite split pebble.

Detail of stones at All Saints Church, Hemblington. Triassic quartzite split pebble.

A medium grained diorite of unknown origin.

A medium grained diorite of unknown origin.

Hertfordshire puddingstone, a form of sarsen.

Hertfordshire puddingstone, a form of sarsen.

Knapped flint with the trace of a fossil echinoid.

Knapped flint with the trace of a fossil echinoid.

Download these notes as a pdf

Bibliography

Candy, I., Lee, J. R. & Harrison, A. M. (Eds.), 2008, The Quaternary of northern East Anglia., Quaternary Research Association., 263 pp.

Hart, S., 2000, Flint architecture of East Anglia., Giles de la Mare Publishers Ltd., London., 150 pp.

Norfolk Heritage Explorer

[1]According to Candy et al. (2008), the pre-Anglian Wroxham Crag and associated Bytham Gravel Beds contain a clastic component dominated by pebbles and cobbles of vein quartz, Triassic quartzite, ‘schorl’, Carboniferous chert, RhaxellaChert, flint and chatter-marked flint. The Bytham River flowed from the English Midlands, eastwards into the North Sea and provided a sediment source for the Wroxham Crag. The Wroxham Crag is differentiated from the underlying Norwich Crag by the presence of these ‘far travelled pebbles’.